Newton's Second Law

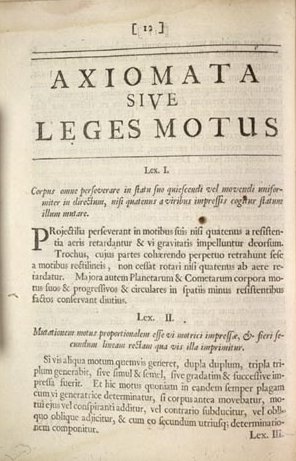

Isaac Newton's Laws of Motion were first published in Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687). Newton used them to prove many results concerning the motion of physical objects. In the third volume (of the text), he showed how, combined with his law of universal gravitation, the laws of motion would explain Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

Newton's first law: law of inertia

Lex I: Corpus omne perseverare in statu suo quiescendi vel movendi uniformiter in directum, nisi quatenus a viribus impressis cogitur statum illum mutare.

- Unless acted upon by an unbalanced force, an object will maintain a constant velocity.

Note: Velocity is a vector, therefore a constant velocity is defined as a constant speed on an unchanging path, or direction.

This law is also called the Law of Inertia or Galileo's Principle.

An object may be acted upon by many forces and maintain a constant velocity so long as these forces are balanced. For example, a rock resting upon the Earth keeps a constant velocity (in this case, zero) because the downward force of its weight balances out the upward force (called the normal force) which the Earth exerts upwardly on the rock. Only unbalanced forces induce acceleration, or a change in the velocity or an object. If you push someone, he or she will accelerate in the direction of the unbalanced force which you have provided (called the applied force). Likewise if you roll a ball along the floor, the unbalanced force of friction will decelerate the ball from some positive velocity to rest.

Before Galileo, people agreed with Aristotle that a body's natural state was at rest, and that movement needed a cause. This is understandable, since in everyday experience, moving objects eventually stop because of friction (except for celestial objects, which were deemed perfect). Moving from Aristotle's "A body's natural state is at rest" to Galileo's discovery was one of the most profound and important discoveries in physics.

There are no true examples of the law, as friction is usually present, and even in space gravity acts upon an object, but it serves as a basic axiom for Newton's mathematical model from which one could derive the motions of bodies from elementary causes: forces.

Newton's second law: fundamental law of dynamics

Lex II: Mutationem motus proportionalem esse vi motrici impressae et fieri secundum lineam rectam qua vis illa imprimitur.

Newton's second law as originally stated in terms of momentum is

'An applied force is equal to the rate of change of momentum'.

<math>d\mathbf{p}/dt=\mathbf{F}</math>.

The physical meaning of this equation is that objects interact by exchanging momentum, and they do this via a force. When the mass of an object is varying, this form is valid, and the <math>\mathbf{a}=\mathbf{F}/m</math> form is not. The statement in terms of momentum is also valid in special relativity if we express the momentum as <math>\mathbf{p}=\gamma m\mathbf{v}</math>, where <math>\gamma</math> is <math>1/\sqrt{1-v^2/c^2}</math>.

If the mass is constant, the force-momentum equivalence reduces to:

The acceleration of an object equals the net force acting on it, divided by its (constant) mass,

- <math>\mathbf{a}=\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{net}}/m</math>

where

- <math> m </math> is the mass of the object,

- <math> \mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{net}} </math> is the net force acting on the object

- <math> \mathbf{a} </math> is the object's acceleration, i.e., the rate of change of its velocity with respect to time

For example, if a bowstring exerts a constant force of 100 newtons on an arrow having a mass of 0.10 kg, then the arrow's acceleration will be 1000 m/s2 until it leaves the bow (after which the arrow will stop speeding up).

When the forces on the object all act along the same line, they can be added as positive and negative numbers, depending on their direction. When they do not all act along the same line, the total must be found by vector addition.

The quantity m, or mass, is a characteristic of the object. The greater the total force acting on an object, the greater the change in its acceleration will be. This equation, therefore, indirectly defines the concept of mass. In the equation, F = ma, a is directly measurable but F is not. The second law only has meaning if we are able to assert, in advance, the value of F. Rules for calculating force include Newton's law of universal gravitation.

Newton's third law: law of reciprocal actions

Lex III: Actioni contrariam semper et aequalem esse reactionem: sive corporum duorum actiones is se mutuo semper esse aequales et in partes contrarias dirigi.

- All forces occur in pairs, and these two forces are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

As shown in the diagram opposite, the skaters' forces on each other are equal in magnitude, and opposite in direction. Although the forces are equal, the accelerations are not: the less massive skater will have a greater acceleration due to Newton's second law. If a basketball hits the ground, the basketball's force on the Earth is the same as Earth's force on the basketball. However, due to the ball's much smaller mass, Newton's second law predicts that its acceleration will be much greater. Not only do planets accelerate toward stars; but, stars accelerate toward planets.

The two forces in Newton's third law are of the same type, e.g., if the road exerts a forward frictional force on an accelerating car's tires, then it is also a frictional force that Newton's third law predicts for the tires pushing backward on the road.

The forces acting between particles A and B lie along parallel lines, but need not lie along the line connecting the particles. One example of this is a force on an electric dipole due to a point charge, when the dipole points in a direction perpendicular to the line connecting the point charge and the dipole. The force on the dipole due to the point charge is perpendicular to the line connecting them, so there is a reaction force on the point charge in the opposite direction, but these two force vectors are parallel and, even when extended to a line, they never cross each other in space.

Also see: Physics Study Guide

Importance and range of validity

Newton's laws were verified by experiment and observation for over 200 years, and they are excellent approximations at the scales and speeds of everyday life. At the atomic scale, they become a poorer approximation to quantum mechanics, and at speeds comparable to the speed of light, they become a poorer approximation to relativity. Just as they fail for material objects moving at speeds close to the speed of light, they fail for light itself.

Newton's first law appears to be a special case of the second law, and Newton may have stated the first law separately simply in order to throw down the gauntlet to the Aristotelians. However, many modern physicists prefer to think of the First Law as defining the reference frames in which the other two laws are valid. These reference frames are called inertial reference frames or Galilean reference frames, and are moving at constant velocity, that is to say, without acceleration. (Note that an object may have a constant speed and yet have a non-zero acceleration, as in the case of uniform circular motion. This means that the surface of the Earth is not an inertial reference frame, since the Earth is rotating on its axis and orbits around the Sun. However, for many experiments, the Earth's surface can safely be assumed to be inertial. The error introduced by the acceleration of the Earth's surface is minute.)

Relationship to the conservation laws

The laws of conservation of momentum, energy, and angular momentum are of more general validity than Newton's laws, since they apply to both light and matter, and to both classical and non-classical physics. In the special case of a system of material particles interacting via instantaneously transmitted forces, Newton's second law can be viewed as a definition of force, and the third law can be derived from conservation of momentum.

Newton stated the third law within a world-view that assumed instantaneous action at a distance between material particles. We now know that this is not the way the universe really works, although it may be a good approximation under certain circumstances. For example, the electrons in the antenna of a radio transmitter do not act directly on the electrons in the receiver's antenna. Momentum is handed off from the transmitter's electrons to the radio wave, and then to the receiver's electrons, and the whole process takes time. Conservation of momentum is satisfied at all times, but Newton's laws are inapplicable, because, for example, the second law does not apply to the radio wave.

Some authors refer to a "strong form" of Newton's third law, which requires that, in addition to being equal and opposite, the forces must be directed along the line connecting the two particles (or the centers of mass of the two objects). The strong form does not always hold. For example, the force between two bar magnets will in general not satisfy the strong form. (Although the bar magnets are not point particles, the same applies, for example, to point particles that have magnetic dipole moments.) In cases where the strong form applies (or where the forces involved are contact forces), Newton's laws can be used to prove conservation of angular momentum. However, this is somewhat misleading, because conservation of angular momentum is always valid, and Newton's laws are not. For example, conservation of angular momentum is valid for electromagnetic fields and their interactions with material particles, but Newton's laws do not apply to electromagnetic waves, and the strong form of the third law is violated even for static electrical and magnetic interactions.

Conservation of energy was discovered nearly two centuries after Newton's lifetime, the long delay occurring because of the difficulty in understanding the role of microscopic and invisible forms of energy such as heat and infra-red light. For a classical system of material particles, conservation of energy, combined with Galilean relativity, implies conservation of momentum, and conservation of momentum implies Newton's laws.

See also

References

- Marion, Jerry and Thornton, Stephen. Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems. Harcourt College Publishers, 1995. ISBN 0030973023

External links

- Newtonian Physics - an on-line textbook

- Motion Mountain - an on-line textbook

- Trajectory Video - video clip showing exchange of momentum